Progress, man’s distinctive mark alone, Not God’s, and not the beasts’: God is, they are; Man partly is, and wholly hopes to be. — Robert Browning

Gorgeous evocations of the lost “modern” world of our dearly departed 20th century, William Steiger’s paintings of hovering dirigibles, looming water towers, and the majestic steel riggings of span bridges are testaments to the wonder of industry and the ghost-like presence of humankind’s aspirations embodied in these forms. The work evokes other structural specters: the decaying World’s Fair sites in Knoxville and Queens, New Jersey’s Pulaski Skyway and the myriad once-vital and now abandoned industries that dot the American landscape. Suggesting a fairground after the crowds have departed or the eerie calm of a factory whose workers have abandoned its enormous machines, Steiger’s work exudes a solemn quiet and heroic nobility. His paintings implore us to step back to finally appreciate the forgotten architecture of human invention and the idealism that inspired such achievements.

Steiger’s meticulously rendered paintings flirt with abstraction and representation to achieve a unique formal language characterized by historical tension between past and present. With their subway tunnels and oil derricks, the paintings represent structures which epitomize progress, movement, technology and the advancing human push. The works are also assertions of a technologically-determined perspective. The aerial view of a landscape of patchwork fields intersected by a snaking river in “Winding River” is a perspective defined by aircraft. The low angles of towers in “Watertower 130 ft high” and mid-flight view of a zeppelin in “5 Sept 10” imply a vantage defined by photography—the invention which more than any other has ordered our perception of the contemporary landscape.

The artist’s rendition of a steel bridge in “Centerspan” and his soaring “Parachute Drop” are perspectives designed to elicit awe. Such works imply the gaze of ant-sized men surveying the heights of their accomplishments, and humbled physically and emotionally by the scale of what they have created.

Emphasizing the grandeur and colossal size of his objects like the zeppelin in “5 Sept 10” whose length is shown spanning acres of land, or the intricacy of the lacework structure of “Parachute Drop,” Steiger recalls an era of industrial exploration—when the same sense of amazement that greeted Lindbergh’s Trans-Atlantic crossing or the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower at the 1889 Paris fair showed a humankind still astounded by the breadth of its accomplishments. The low angles often emphasized in these paintings (which allow Steiger’s structures to ascend to the ranks of myth-making) emphasize this majesty in feats now taken for granted: the ability to float above the world or travel through an underwater tunnel or survey the landscape for miles from the crest of Steiger’s “Wonderwheel.”

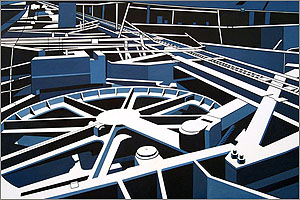

Evoking a period in which architectural accomplishments were praised for their sheer size and functionality (conquering gravity, harnessing the power of the elements, allowing humankind dominion over nature) rather than for their surface beauty, works like “Roundhouse,” of a facility for breaking down and sorting train cars, stress the ingenuity of design and engineering in such utilitarian creations.

These paintings suggest a time of innocent wonder which thrilled equally to the fairground ride as to the dirigible sailing silently across the sky. Steiger names his view of an amber tower whose background is crisscrossed by powerlines “Watertower 130 ft high.” It is the sort of inscription one might find on a vintage postcard, and contains an amusing boast of the comparable heights of human advancement, where indoor plumbing and the Golden Gate Bridge constitute the 8th and 9th wonders of the modern world. The artist’s subway “Tunnel” and “NP Railroad Bridge”—and the progress and movement they convey—are our pyramids, our hanging gardens of Babylon, our Notre Dame—the emblems of a young country founded on a future daily reenvisioned. That sense of amazement at, what seem in hindsight, such small marks of progress, invests the work with a never-to-be-recaptured guilelessness and belief. Steiger’s paintings are windows to a “once-upon-a-time” in which technology offered salvation...when the physical world was the culmination of utopian possibility glimpsed all around us. These oil derricks and dirigibles allow us to penetrate the ground and the heavens both and thus rise supreme over our constructed dreamland. Implicitly rejecting jaded postmodern reassessments of history, Steiger recaptures the thrill of modernity.

A celebration of the grandeur of form as active and alive, the work references the photographs of Lewis Hine, Charles Sheeler’s portrait of a 1927 Detroit Ford Plant or Albert Renger-Patzsch's 1927 photograph of “Blast Furnaces” as well as a more melancholy strain reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s comparably stripped-down America-scapes.

Steiger’s work itself exists in a charmed limbo, one where disasters are as minimally traumatic as the minor snafus of “Accident #1” and “Accident #2” in which a biplane balances awkwardly, like a discarded child’s toy, on its nose, as if dropped softly from the heavens. The world of Steiger’s paintings depicts an age before supersonic speeds and the ferocious impacts they entail, a world of gentle hope where fairground ferris wheels bear sweetly fanciful names like “Wonderwheel.” From the majestic, unassailable girders of “NP Railroad Bridge” to the intricacy of “Wonderwheel” and the zeppelin in “5 Sept 10,” these disparate images nevertheless convey a suggestively gentle, subtle turning, sailing movement; the soft breeze of open air and the comforting metallic groans and clinks of enormous contraptions built to do our bidding.

The work shows what compelling, romantic histories can be inspired by forgotten and abandoned things—how objects themselves often speak a more tantalizing, epic and emotionally resonant history than all the books and memorials devoted to human excellence. Steiger’s images are unofficial memorials honoring what was as the foundation of what is to come.

With their blank, detail-less backgrounds (save a cloudy sky or retreating telephone line) and minimalist rendering, Steiger’s paintings suggest blueprints or coloring book templates or the engravings which accompany encyclopedia entries—an iconography of industrial interconnection via airplane, train and bridge pared down to its cleanest, barest essence. The simplicity of Steiger’s rendering gives his “NP Railroad Bridge” and “Roundhouse” a crispness unsullied by age or use. Like memories themselves, these objects dwell in an impermeable bubble of timeless perfection that marks the headline-making day they first appeared—the first journey of the zeppelin, the first spin of the “Wonderwheel.”

Steiger’s color scheme is comparably basic. His limited palette of blacks, woolen greys, olives, and an occasional assertion of yellow ochre or kidney brown is evocative of early two- and three-color printing processes. Steiger’s muted, earthtone color scheme suggests scenes of faded memory and mimics the antiquated look of sepia photographs and rusted parts asserting the essential theme of his work: that these monuments of progress are also memorials to a bygone age.

The downside of progress is obsolescence, and Steiger’s planes and towers are often suggestive of the faded glory of another time. Steiger’s ghosts in the machine perspective captures the melancholy in a retreating wonderland. No image is more indicative of that ethereal, ghostly, lost place than a fairground whirligig ride “The Flying Machine,” that spins little rowboats on metal tethers. William Steiger’s museum of industry celebrates a comparable effort to fly, to sail away, a hopefulness embodied in our forms.